Storyforming

Chapter 8

Introduction to Storyforming

Inspiration

When an author begins work on a story, he seldom has the whole thing figured out in advance. In fact, he might start with nothing more than a bit of action, a scrap of dialogue, or perhaps only a title. The urge to write springs from some personal interest one wants to share. It could be an emotion, an experience, or a point of view on a particular subject matter. Once inspiration strikes, however, there is the compelling desire to find a way to communicate what one has in mind.

Another thing usually happens along the way. One creative thought leads to another, and the scope of what one wishes to communicate grows from a single item into a collection of items. Action suggests dialogue that defines a character that goes into action, and on and on. Eventually, an author finds himself with a bag of interesting dramatic elements, each of which is intriguing, but not all of which connect. It is at this point an author’s mind shifts gears and looks at the emerging work as an analyst rather than as a creator.

Structure

The author as analyst examines what he has so far. Intuitively he can sense that some structure is developing. The trick now is to get a grip on the “big picture.” Four aspects of this emerging story become immediately clear: Character, Theme, Plot, and Genre. An author may find the points of view expressed by certain characters are unopposed in the story, making the author’s point of view seem heavy-handed and biased. In other places, logic fails, and the current explanation of how point A got to point C is incomplete. He may also notice that some kind of overall theme is partially developed, and the entire work could be improved by shading more dramatic elements with the same issues.

So far, our plucky author has still not created a story. Oh, there’s one in there somewhere, but there’s much to do to bring it out. For one thing, certain items he’s developed may begin to seem out of place. They don’t fit in with the feel of the work as a whole. Also, certain gaps have become obvious which beg to be filled. In addition, parts of a single dramatic item may work and other parts may not. For example, a character may ring true at one moment, but turn into a clunker the next.

Having analyzed, then, the author sets about curing the ailments of his work in the attempt to fashion it into a complete and unified story. Intuitively, an author will examine all the logical and emotional aspects of his story, weed out irregularities and fill in cracks until nothing seems out of place in his considerations. Just as one might start with any piece of a jigsaw puzzle, so the story eventually fills the author’s heart and mind as a single, seamless, and balanced item, greater than its parts. In the end, a larger picture emerges. The story takes on an identity all its own.

Communication

Looking at the finished story, we can tell two things right off the bat. First, there is a certain logistic dramatic structure to the work. Second, that structure is expressed in a particular way. In Dramatica, we call that underlying deep dramatic structure a Storyform. The manner in which it is communicated is the Storytelling.

As an example of how the Storyform differs from the Storytelling, consider Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story. The dramatics of both stories are essentially the same, yet the expression of those dramatics is different. Storytelling dresses the dramatics in different clothes, couches the message in specific contexts, and brings added non-structure material to the work.

The structure of a story is like a vacant apartment. Everything is functional, but it doesn’t have a personality until someone moves in. Over the years, any number of people might occupy the same rooms, working within the same functionality but making the environment uniquely their own. Similarly, the same dramatic structures have been around for a long time. Yet, every time we dress them up in a way we haven’t seen before, they become new again. So, part of what we find in a finished work is the actual Grand Argument Story form and part is the Storytelling.

The problems most writers face arise from the fact that the creative process works on both storyform and storytelling at the same time. The two become inseparably blended, so trying to figure out what needs fixing is like trying to determine the recipe for quiche from the finished pie. It can be done, but it is tough work. What is worse, an author’s personal tastes and assumptions often blind him to some of the obvious flaws in the work, while overemphasizing others. This can leave an author running around in circles, getting nowhere.

Fortunately, another pathway exists. Because the eventual storyform outlines all the essential feelings and logic produced by a story, an author can begin by creating a storyform first. Then, all that follows will work together because it is built on a consistent and solid foundation.

To create a storyform, an author needs to decide about the kinds of topics he wishes to explore and the kinds of impact he wishes to have on his audience. This can sometimes be a daunting task. Most authors prefer to stumble into the answers to these questions during the writing process, rather than deliberate over them in advance. Still, with a little consideration up front, much grief can be prevented later as the story develops.

If you’re a non-structural writer, try writing first and create the storyform afterward.

Audience Impact

There are eight questions about a story that are so important and powerful that we refer to them as the essential questions. Determining the answers to these can instantly clarify an embryonic story idea into a full-fledged story concept. Four of the questions refer to the Main Character and four refer to the overall Plot. Taken together, they crystallize how a story feels when it is over, and how it feels getting there.

Choosing Without Losing

When given multiple choices in Dramatica, choosing an answer does not exclude the remaining choices. A grand argument story has all the pieces in every story. Making choices arranges the structural items with the story points. All dynamic choices appear in every story. Where they appear and how they relate to the story are controlled by the choices you make.

Character Dynamics

Both structure and dynamics can be seen at work in characters. We see structural relationships most easily in the Objective Characters who serve to illustrate fixed dramatic relationships that define the potentials at work in a story from an objective point of view. We see dynamic relationships more easily in the Subjective Characters who serve to illustrate growth in themselves and their relationships over the course of a story.

The Subjective Characters are best described by the forces that drive them, rather than by the characteristics they contain. These forces are most clearly seen (and therefore best determined) for the Main Character. There are four Dynamics that determine the nature of the Main Character’s problem-solving efforts. The four Character Dynamics specify the shape of the Main Character’s growth. Let’s explore each of the four essential character dynamics and their impact on the story as a whole.

Main Character Resolve: Change or Steadfast?

The first Essential Character Dynamic determines if the Main Character is a changed person at the end of a story. From an author’s perspective, selecting Change or Steadfast sets up the kind of argument made about the effort to solve the story’s problem.

There are two principal approaches through which an author can illustrate the best way to solve the Problem explored in a story. One approach is to show the proper way of going about solving the Problem. The other is to show the wrong way to solve the Problem.

- To illustrate the proper way, your Main Character must hold on to his Resolve and remain Steadfast if he is to succeed, because he believes he is on the right path.

- To illustrate the improper way of dealing with a Problem, your Main Character must change to succeed, for he believes he is going about it the wrong way.

Of course, Success is not the only Outcome that can happen to a Main Character. Another way to illustrate that an approach for dealing with a Problem is proper would be to have the Main Character Change his way of going about it and fail. Similarly, a Main Character that remains Steadfast and fails can illustrate the improper way.

So, choosing Change or Steadfast has nothing directly to do with being correct or mistaken; it just describes whether the Main Character’s final Resolve is to stay the course or try a different tack.

Just because a Main Character should remain Steadfast does not mean he doesn’t consider changing. In fact, the alternative to give up or alter his approach in the face of ever-increasing opposition is a constant temptation.

Even if the Main Character remains steadfast despite difficulties and suffering, the audience may still not want him to succeed. This is because simply being steadfast does not mean one is correct.

If the audience sees that a character remains steadfast yet misguided, the audience will hope for his eventual failure.

Similarly, a Change Main Character does not mean he is changing all the time. Usually, the Change Main Character will resist change until he’s forced to choose. At that point, the Main Character must choose to continue down his original path, or to jump to the new path by accepting change in himself or his outlook.

Regardless of the benefits to be had by remaining steadfast, the audience will want the Change Main Character finally to succeed if he is on the wrong path and changes. However, if he does not change, the audience will want him to lose all the benefits he thought he had gained.

Your selection of Change or Steadfast has wide-ranging effects on the dynamics of your story. Such things as the relationship between the Overall Story and Relationship Story Throughlines link to this dynamic. Even the order of exploration of your thematic points adjusts in the Dramatica model to create and support your Main Character’s decision to change or remain steadfast.

Examples of Main Character Resolve:

Change Main Characters: Hamlet in Hamlet; Frank Galvin in The Verdict; Wilber in Charlotte’s Web; Rick in Casablanca; Michael Corleone in The Godfather; Scrooge in A Christmas Carol; Nora in A Doll’s House

Steadfast Main Characters: Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie; Jake Gittes in Chinatown; Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs; Chance Gardener in Being There; Job in the Bible.

The Influence Character Resolve

The Influence Character has a Resolve that is the inverse of the Main Character’s. When the Main Character is a Change character, the Influence Character remains Steadfast (such as the Ghosts in A Christmas Carol, Viola De Lesseps in Shakespeare In Love, and the steadfast Impact of Ricky Fitts in American Beauty). When the Main Character remains Steadfast, the Influence Character CHANGEs (such as Sam Gerard in The Fugitive, Blanche Hudson in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, and Raymond Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate). It is not important whether it’s the steadfastness of one character that forces the change in the other, or the change in one that supports the steadfastness of the other. What is important is that the inverse relationship between the Main Character’s Resolve and the Influence Character’s Resolve provides a key point of reference for an audience’s understanding of your story’s meaning.

Examples of Influence Character Resolve:

Steadfast Influence Characters: The Ghost of King Hamlet in Hamlet; Laura Fischer in The Verdict; Charlotte in Charlotte’s Web; Ilsa in Casablanca; Kaye Corleone in The Godfather; The Ghosts in A Christmas Carol; Torvald in A Doll’s House

Change Influence Characters: Jim O’Connor in The Glass Menagerie; Evelyn Mulwray in Chinatown; Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs; Dr. Allenby in Being There; Satan in the Bible.

Main Character Growth: Stop or Start?

The second essential question determines the direction of the Main Character’s growth.

While the Main Character Resolve focuses on the results of the MC’s response to his inequity, the part of Dramatica that focuses on the Main Character’s “character arc” is call the Main Character Growth.

Like any well constructed argument, you must build to your conclusions—you can’t just jump right to the end and expect anyone to accept it. The Main Character must go through the process of growth that gets him to a position where he can see the problem for what it is and deal with it directly.

Whether a Main Character eventually Changes his nature or remains Steadfast, he will still grow over the course of the story, as he develops new skills and understanding. This growth has a direction.

Either he will grow into something (Start) or grow out of something (Stop).

A Change Main Character grows either by adding a characteristic he lacks (Start) or by dropping a characteristic he already has (Stop). Either way, his makeup alters in nature. As an example we can look to Ebenezer Scrooge in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Does Scrooge need to Change because he is miserly or because he lacks generosity? Scrooge’s problems do not stem from his active greed, but from his passive lack of compassion. It is not that he is on the attack, but that he does not actively seek to help others. This reflects a need to Start, rather than Stop. This difference is important to place the focus of conflict so it supports the overall argument of the story.

In contrast, Steadfast Main Characters will not add nor delete a characteristic, but will grow either by holding on against something bad, waiting for it to Stop, or by holding out until something good can Start.

For a Steadfast Character, growth is not a matter of Change, but a matter of degree. Change is still of concern to him but in his environment, not in himself. Conversely, a Change Character actually alters his being, under the influence of situational considerations. This helps clarify why it is often falsely thought that a Main Character MUST Change, and why Steadfast characters are thought not to grow.

To develop growth in a Main Character properly, one must decide whether he is Change or Steadfast and the direction of the growth.

A good way to get a feel for this dynamic in Change Characters is to picture the Stop character as having a chip on his shoulder and the Start character as having a hole in his heart. If the actions or decisions taken by the character are what make the problem worse, then he needs to Stop. If the problem worsens because the character fails to take certain obvious actions or decisions, then he needs to Start.

Of course, to the character, neither of these perspectives on the problem is obvious, as he must grow and learn to see it. Often the audience sees another view the character does not get: The objective view. The audience can empathize with the character’s failure to see himself as the source of the problem even while recognizing that he should or should not change. It is here that Start and Stop register with the audience as being obvious.

Essentially, if you want to tell a story about someone who learns he has been making the problem worse, choose Stop. If you want to tell a story about someone who has allowed a problem to become worse, choose Start.

A Steadfast Main Character’s Resolve needs to grow regardless of Start or Stop. If he is a Start Character, he will be tempted by signs the wanted outcome is not going to happen or is unattainable. If he is a Stop Character, he will find himself pressured to give in.

Remember that we see Growth in a Steadfast Character largely in his environment. We see his personal growth as a matter of degree.

Examples of Main Character Growth:

Start Characters: Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie; Rick in Casablanca; Scrooge in A Christmas Carol; Nora in A Doll’s House

Stop Characters: Hamlet in Hamlet; Frank Galvin in The Verdict; Wilber in Charlotte’s Web; Jake Gittes in Chinatown; Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs; Chance Gardener in Being There; Job in the Bible; Michael Corleone in The Godfather

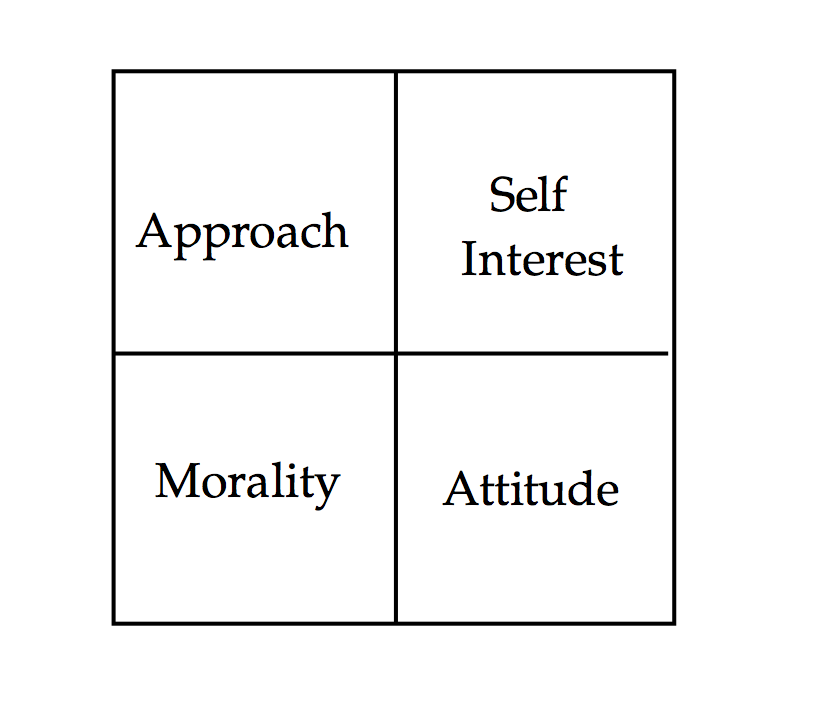

Main Character Approach: Do-er or Be-er?

The third essential question determines the Main Character’s preferential approach to problem solving.

By temperament, Main Characters (like each of us) have a preferential method of approaching Problems. Some would rather adapt their environment to themselves through action; others would rather adapt their environment to themselves through strength of character, charisma, and influence.

There is nothing intrinsically right or wrong with either Approach, yet it does affect how one will respond to Problems.

Choosing Do-er or Be-er does not prevent a Main Character from using either Approach, but merely defines the way they are likely to first Approach a Problem. The Main Character will only use the other method if their preferred method fails. Having a preference does not mean being less able in the other area.

Do not confuse Do-er and Be-er with active and passive. If we see a Do-er as active physically, we see a Be-er as active mentally. While the Do-er jumps in and tackles the problem by physical maneuverings, the Be-er jumps in and tackles the problem with mental deliberations. For example, Harry Callahan in Dirty Harry is an aggressive Do-er. A bank robbery happens while he eats lunch. He walks out and shoots some bad guys, all the time munching on his hot dog—definitely an active Do-er. Hamlet, from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, is a classic Be-er. His approach to expose his murderous uncle is to change himself by pretending to be crazy. He’s so aggressive with his “being” that it drives his girlfriend insane.

The point is not which one is more motivated to hold his ground but how he tries to hold it.

A Do-er would build a business by the sweat of his brow.

A Be-er would build a business by attention to the needs of his clients.

Obviously both Approaches are important, but Main Characters, just like the real people they represent, will have a preference.

A martial artist might choose to avoid conflict first as a Be-er character, yet be capable of beating the tar out of an opponent if avoiding conflict proved impossible.

Similarly, a schoolteacher might stress exercises and homework as a Do-er character, yet open his heart to a student who needs moral support.

When creating your Main Character, you may want someone who acts first and asks questions later, or you may prefer someone who avoids physical conflict if possible, then lays waste the opponent if they won’t compromise.

A Do-er deals in competition, a Be-er in collaboration.

The Main Character’s affect on the story is both one of rearranging the dramatic potentials of the story, and one of reordering the sequence of dramatic events.

Examples of Main Character Approach:

Do-er Characters: Frank Galvin in The Verdict; Wilber in Charlotte’s Web; Jake Gittes in Chinatown; Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs; Michael Corleone in The Godfather.

Be-er Characters: Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie; Rick in Casablanca; Scrooge in A Christmas Carol; Hamlet in Hamlet; Chance Gardener in Being There; Job in the Bible; Nora in A Doll’s House.

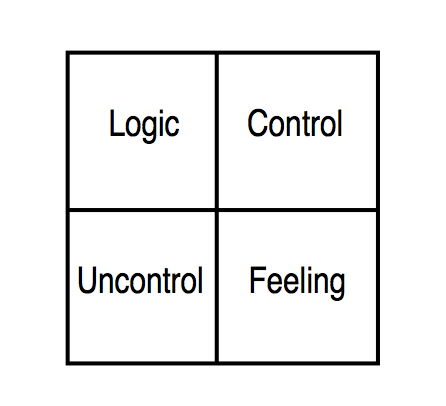

Main Character Problem-Solving Style: Linear or Holistic?

The fourth Essential Character Question determines a Main Character’s problem-solving techniques to be linear or holistic.

Much of what we do as individuals is learned behavior. Yet, the basic operating system of the mind is cast biologically before birth as being more sensitive to space or time. Each of us has a sense of how things are arranged (space) and how things are going (time), but which one filters our thinking determines our Problem-Solving Style as being Linear or Holistic, respectively.

Linear Problem-Solving Style describes spatial thinkers who tend to use linear Problem solving as their method of choice. They set a specific Goal, determine the steps necessary to achieve that Goal, and then embark on the effort to carry out those steps.

Holistic Problem-Solving Style describes temporal thinkers who tend to use holistic Problem solving as their method of choice. They get a sense of the way they want things to be, find out how things need to balance to bring about those changes, and then make adjustments to create that balance.

While life experience, conditioning, and personal choice can go a long way toward counterbalancing those sensitivities, underneath all our experience and training the tendency to see things chiefly in terms of space or time remains. In dealing with the psychology of Main Characters, it is essential to understand the foundation on which their experience rests.

How can we illustrate the Problem-Solving Style of our Main Character? The following point-by-point comparison provides some clues:

- Holistic: Looks at motivations Linear: Looks at purposes

- Holistic: Tries to see connections Linear: Tries to gather evidence

- Holistic: Sets up conditions Linear: Sets up requirements

- Holistic: Determines the leverage points that can restore balanceLinear: Breaks a job into steps

- Holistic: Seeks fulfillment Linear: Seeks satisfaction

- Holistic: Concentrates on “Why” and “When”Linear: Concentrates on “How” and “What”

- Holistic: Puts the issues in context Linear: Argues the issues

- Holistic: Tries to hold it all together Linear: Tries to pull it all together

In stories, more often than not, physical gender matches Problem-Solving Style. Occasionally, however, gender and Problem-Solving Style are cross-matched to create unusual and interesting characters. For example, Ripley in Alien and Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs are Linear Problem-Solving Style women. Tom Wingo in The Prince of Tides and Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October are Holistic Problem-Solving Style men. In most episodes of The X Files, Scully (the Holistic F.B.I. agent) is Linear Problem-Solving Style and Mulder (the Linear F.B.I. agent) is Holistic Problem-Solving Style, which explains part of the series’ unusual feel. Note that Problem-Solving Style has nothing to do with a character’s sexual preferences or tendency toward being masculine or feminine in mannerism —it simply deals with the character’s problem-solving techniques.

Sometimes stereotypes are spread by what an audience expects to see, which filters the message and dilutes the truth. By placing a Holistic psyche in a physically Linear character or a Linear psyche in a physically Holistic character, preconceptions no longer prevent the message from being heard. On the downside, some audience members may have trouble relating to a Main Character whose problem-solving techniques do not match the physical expectations.

Examples of Main Character Problem-Solving Style:

Holistic Problem-Solving Style Characters: Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie; Nora in A Doll’s House; Tom Wingo in The Prince of Tides

Linear Problem-Solving Style Characters: Frank Galvin in The Verdict; Wilber in Charlotte’s Web; Jake Gittes in Chinatown; Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs; Michael Corleone in The Godfather; Rick in Casablanca; Scrooge in A Christmas Carol; Hamlet in Hamlet; Chance Gardener in Being There; Job in the Bible

Wrapping Up Character Dynamics

We have presented four simple questions. Knowing the answers to these questions provides a strong sense of guidelines for an author in framing his message. The one seeming drawback is that each of the questions appears binary in nature, which can easily lead to concerns that this kind of approach produces an excessively structured or formulaic story. One should keep in mind that this is just the first stage of communication. Storyforming creates a solid structure on which the other three stages can be built.

As we advance through this process, we shall learn how the remaining three stages bring shading, tonality, and more of a gray-scale feel to each of these questions. For example, the question of Resolve leads to other questions in each of the other stages. One question controls how strongly the Main Character has embraced change or how weakly he now clings to his steadfastness. Another controls how big the scope of the change is or how small the attitudes that didn’t budge are. Yet another controls how much change or steadfast matters to the state of things in the story: Will it alter everything or just a few things in the big pond. In the end, the Character Dynamics firmly yet gently mold the point of view from which the audience receives its most personal experiences in the story.

Plot Dynamics

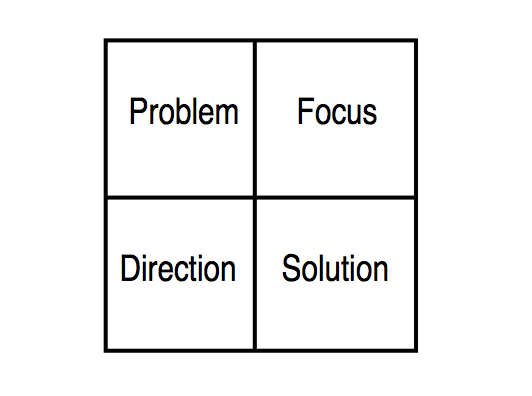

As with characters, both structure and dynamics can be seen at work in Plot. Most of the plot dynamics center on the Overall Story, but affect all four throughlines. The following four questions decide the controlling events in the story, the scope of the story, the story’s final resolution, and the plot’s connection to the Main Character’s outlook.

Overall Story Driver: Action or Decision?

Action or Decision describes how the story is driven forward. The question is: Do Actions precipitate Decisions or do Decisions drive Actions?

At the end of a story there will be an essential need for an Action to be taken and a Decision to be made. However, one of them will be the roadblock that must be removed first to enable the other. This causal relationship is felt throughout the story where either Actions would never happen on their own, except that Decisions keep forcing them, or Decisions would never be made except that Actions leave no other choice than to decide. In fact, the “inciting event” that causes the story’s Problem will also match the kind of Driver required to resolve it. This “bookends” a story so its problem and solution are both precipitated by the same kind of Driver: Action or Decision.

Stories contain both Action and Decision. Choosing one does not exclude the other. It merely gives preference to one over the other. Do Actions precipitate Decisions, or do Decisions precipitate Actions?

This preference can be increased or nearly balanced out by other dynamic questions you answer about your story. It’s a matter of the background against which you want your Main Character to act.

The choice of background does not have to reflect the nature of the Main Character. In fact, some interesting dramatic potentials emerge when they do not match.

For example, a Main Character of action (called a Do-er) forced by circumstance to handle a deliberation-type problem finds himself struggling for the experience and tools he needs to do the job.

Similarly, a deliberating Main Character (called a Be-er) would find himself whipped into turmoil if forced to resolve a problem needing action.

These mixed stories appear everywhere from tragedy to comedy and can add an extra dimension to an otherwise one-sided argument.

Since a story has both Actions and Decisions, it is a question of which an author wants to come first: Chicken or egg? By selecting one over the other, you direct Dramatica to set up a causal order between dynamic movements in the Action line and the Decision line.

The Story Driver drives the Overall Story, not the Main Character (except in the Main Character’s capacity as a player in the Overall Story throughline). The Main Character Approach moderates the Main Character’s problem solving methodology.

The Story Driver appears in at least five instances in your story.

- The inciting event—this kicks off the Overall Story by setting things into motion.

- The transition between Overall Story Signpost 1 and Overall Story Signpost 2—this event changes the direction of the story in a significant way and indicates the act break transition

- The transition between Overall Story Signpost 2 and Overall Story Signpost 3—this event changes the direction of the story in a significant way and indicates the act break transition

- The transition between Overall Story Signpost 3 and Overall Story Signpost 4—this event changes the direction of the story in a significant way and indicates the act break transition.

- The concluding event—this event closes the story, or its absence indicates an open-ended story.

In each case, the nature of the event is consistent with the Story Driver. So, a story with a Driver of Action has an action as the inciting event, actions forcing Overall Story Act transitions, and an action to bring the story to a close. A story with a Driver of Decision has a decision (or deliberation) as the inciting event, decisions (or deliberations) forcing Overall Story Act transitions, and a decision (or deliberation) to bring the story to a close.

Consistency is important. Consistency sets up the temporal, causal logistics of the story. Consistency sets up whether actions drive decisions in the story, or decisions drive actions in the story. Order has meaning and the Story Driver controls the order and is part of the storyform dynamics.

ALL STORIES HAVE ACTIONS AND DECISIONS

Choosing the Story Driver does NOT eliminate the unchosen item from the story.

Choosing the Story Driver sets the order of cause and effect. The chosen driver describes the cause. The remaining driver describes the effect.

For example, imagine an American football game with the two teams on the field. The one with the ball is the offensive team. The one on the other side of the line of scrimmage is the defensive team.

In American football, the offensive team is driven by DECISIONS. At the start of each new play, the offensive team gathers together in a huddle and DECIDES what actions they are going to take. Based on their decision, they act accordingly. If you change the decision, the actions that follow necessarily change to accommodate the new decision.

The flip side is true for the defensive team. The defensive team is driven by ACTIONS (specifically, those of the offensive team). Once the offense acts, the defense can decide how best to respond to the actions. For example, if the offense moves all their team members to one side of the field, the defense may decide to change their plan of defense.

What Constitutes A Driver? Is There A Litmus Test?

Actions or Decisions are Story Drivers if they fundamentally change the course of the overall story, such as the five events described earlier. The closest thing to a litmus test is to think of the cause and effect relationship between the Driver and the unchosen driver. Ask yourself, “Would the effects still happen if the cause is removed?” If the answer is, “Yes, the effects still happen,” then your driver does not stand up to the test. If the answer is, “No, the effects would not happen,” then that’s a good indication that it IS a driver.

Let’s look at some examples.

Star Wars (1977) has a Story Driver of Action. The inciting event is the theft of the Death Star plans by the Rebellion. What decisions follow that driver? The Empire decides to disband the Senate, kidnap Princess Leia, and take their secret weapon out of hiding before its completion. If the plans had not been stolen, would the Empire have decided to do the same things within the same time frame? No. The Death Star was not yet complete. The theft of the plans forced the Empire to change plans.

The concluding event in Star Wars (1977) is the destruction of the Death Star. Does it end the overall story? Yes. Was there a decision that could have been made that might have stopped the Empire from destroying the Rebel base? No, none within the framework of the story as presented. (Anything is possible, but the story rules dictated an action must be taken to resolve the conflict in the story—not every conflict in the story’s universe, but the one around which the story revolves.)

The Verdict has a Story Driver of Decision. The inciting event is the decision to give Frank the case. Since that happens before the film begins, let’s say the real” inciting event is the plaintiff’s attorney’s (Frank’s) decision to bring the case to trial. Based on that decision, the defense attorneys send Frank’s key witness to the Caribbean, hire a woman to act as a mole within Frank’s camp, and otherwise stack the legal deck in their favor. Would the defense have done this if the plaintiff’s attorney had chosen to settle? No, their actions would change accordingly.

The concluding event in The Verdict is…the verdict. A verdict is a decision. In this story, it is the decision that draws the OS throughline to a close. Is there an action that could have resolved this story? No. If the case was thrown out, the plaintiff’s case would remain unresolved and the case could come back again in some other form. The verdict, ANY verdict, resolves the story and brings it to a conclusion.

Examples of Story Driver

Action Driven Stories: Hamlet; The Silence of the Lambs; Being There; A Christmas Carol; Rain Man

Decision Driven Stories: The Verdict; Chinatown; The Glass Menagerie; Casablanca; The Godfather; The Story of Job; Charlotte’s Web; A Doll’s House

Overall Story Limit: Timelock or Optionlock?

Limit determines the kind of constraints that bring a story to a conclusion.

For an audience, a story’s limit adds dramatic tension as they wonder if the characters will complete the story’s goal. In addition, the limit forces a Main Character to end his deliberations and Change or Remain Steadfast.

Sometimes stories end because of a time limit. Other times they draw to a conclusion because all options have been exhausted.

A Timelock forces the conclusion by running out of time. A Timelock is either a specific deadline, such as High Noon, or a specific duration of time, such as 48 Hrs. The conflict climaxes when the time is up.

An Optionlock forces the conclusion by running out of options. An Optionlock is either a specific number of options, such as three wishes, or a specific number of conditions, such as the alignment of the planets. The conflict climaxes when the options are exhausted.

Both of these means of limiting the story and forcing the Main Character to decide are felt from early on in the story and get stronger until the story’s climax.

Optionlocks need not be claustrophobic so much as that they provide limited pieces with which to solve the Problem. They limit the scope of the Problem and its potential solutions.

Timelocks need not be hurried so much as they limit the interval during which something can happen. Timelocks determine the duration of the growth of the Problem and the search for solutions.

Choosing a Timelock or an Optionlock has a significant impact on the nature of the tension the audience will feel as the story progresses toward its climax.

A Timelock tends to take a single point of view and slowly fragment it until many things are going on at once.

An Optionlock tends to take many pieces of the puzzle and bring them all together at the end.

A Timelock raises tension by dividing attention, and an Optionlock raises tension by focusing it. Timelocks increase tension by bringing a single thing closer to being an immediate problem. Optionlocks increase tension by building a single thing that becomes a functioning problem.

One cannot look just to the climax to find out if a Timelock or Optionlock is in effect. Indeed, you may tag both Time and Option locks to the end of the story to increase tension.

A better way to gauge the limit at work is to look at the nature of the obstacles thrown in the path of the Protagonist or Main Character. If the obstacles are mainly delays, a Timelock is in effect. If missing essential parts causes the obstacles, an Optionlock is in effect.

An author may feel more comfortable building tension by delays or building tension by missing pieces. Choose the kind of lock most meaningful for you.

Examples of Story Limit

Optionlock Stories: Seven; Hamlet; The Silence of the Lambs; Being There; The Verdict; Chinatown; The Glass Menagerie; Casablanca; The Godfather; The Story of Job; Rain Man; A Doll’s House

Timelock Stories: Charlotte’s Web; American Graffiti; High Noon; 48 hrs; A Christmas Carol; An American President

Overall Story Outcome: Success or Failure?

Although easily tempered by degree, Success or Failure describes whether the Overall Story Characters achieve what they set out to achieve at the beginning of the story. If they do, it is Success. If they don’t, Failure. There is no value judgment involved.

The Overall Story Characters may learn they don’t want what they thought they did, and in the end not go for it. Even though they have grown, this is a Failure—they did not achieve what they originally intended.

Similarly, they may achieve what they wanted and succeed even though they find it unfulfilling or unsatisfying.

The point here is not to pass a value judgment on the worth of their Success or Failure. Simply decide if the Overall Story Characters succeeded or failed in the attempt to achieve what they set out to achieve at the beginning of the story.

For example, Romeo and Juliet is a Success story because the feud between the families is ended at the end of the play after the death of Romeo and Juliet:

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life;

Whole misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark’d love,

And the continuance of their parents’ rage,

Which, but their children’s end, nought could remove

(Romeo and Juliet, Prologue, William Shakespeare)

By contrast, Hamlet is a Failure story. Hamlet is unable to protect his family from his murderous uncle and the entire family is destroyed.

Examples of Story Outcome

Success Stories: The Silence of the Lambs; Being There; A Christmas Carol; The Verdict; Chinatown; Casablanca; The Godfather; The Story of Job; Charlotte’s Web

Failure Stories: Hamlet; The Glass Menagerie; Rain Man; A Doll’s House

Main Character Judgment: Good or Bad?

Judgment determines whether the Main Character resolves his personal angst.

The rational argument of a story deals with practicality: Does the kind of approach taken lead to Success or Failure in the endeavor. In contrast, the passionate argument of a story deals with fulfillment: Does the Main Character find peace at the end of his journey?

If the Main Character’s angst is resolved, then the Main Character is in a Good place on a personal level. If the angst is unresolved, then the Main Character is in a Bad place. It’s important to evaluate the Judgment solely in terms of the Main Character’s personal problems in this story. He may have other personal problems in other contexts, but those are not relevant to picking Good or Bad.

If you want an upper story, you will want Success in the Overall Story and a Judgment of Good.

If you want a tragedy, you will want the objective effort to fail, and the subjective journey to end badly as well.

Life often consists of trade-offs, compromises, sacrifices, and reevaluations, and so should stories. Choosing Success/Bad stories or Failure/Good stories opens the door to these alternatives.

If we choose a Failure/Good story, we imagine a Main Character who realizes he had been fooled into trying to achieve an unworthy Goal and discovers his mistake in time. Or we imagine a Main Character who discovers something more important to him personally while trying to achieve the Goal. We call each of these examples of a personal triumph.

A Success/Bad story might end with a Main Character achieving his dreams only to find they are meaningless, or Main Character who makes a sacrifice for the success of others but ends up bitter and vindictive. Each of these would be a personal tragedy.

Because Success and Failure are measurements of how well specific requirements have been met, they are by nature objective. In contrast, Good and Bad are subjective value Judgments based on a story point of the Main Character’s personal fulfillment.

What is interesting about the Story Outcome and the Story Judgment are how they work independently to provide meaning to the story argument, yet also work together to create additional meaning for the audience.

Examples of Story Judgment

Stories with a Judgment of Good: Being There; A Christmas Carol; The Verdict; Casablanca; Charlotte’s Web; Rain Man; A Doll’s House

Stories with a Judgment of Bad: Hamlet; The Silence of the Lambs; Chinatown; The Godfather; The Glass Menagerie

Storyforming Structural Story Points

By answering the eight essential questions we refine our understanding of the way our story will feel to our audience. The next task is to clarify what it is we intend to talk about. In the Theme section of The Elements of Structure we were introduced to the various Story Points an audience will look for while experiencing and evaluating a story. Now we turn our attention to examining the issues we, as authors, must consider in selecting our Story Points. We begin with the Story Points that most affect Genre, then work our way down through Plot and Theme to arrive at a discussion of what goes into selecting a Main Character’s Problem.

Selecting the Throughlines in your story

One of the easiest ways to identify the four Throughlines in your story (Overall Story, Relationship Story, Main Character, and Influence Character) is by looking at the characters that appear in each Throughline. Who are they? What are they doing? What are their relationships to one another? Clearly identifying the characters in each throughline will make selecting the thematic Throughlines, Concerns, Issues, and Problems for the throughlines easier.

For the Overall Story Throughline:

When looking at the characters in the Overall Story Throughline, identify them by the roles they play instead of their names. This keeps them at a distance, making them a lot easier to evaluate objectively. For instance, some of the characters in Shakespeare’s Hamlet might be the king, the queen, the ghost, the prince, the chancellor, and the chancellor’s daughter. Characters in The Fugitive might be the fugitive doctor, the federal marshal, the dead wife, the one-armed man, and so on. By avoiding the characters’ proper names you also avoid identifying with them and confusing their personal concerns with their concerns as Overall Story Characters.

Aren’t the Main Character and the Influence Character also part of the Overall Story?

The Main Character and the Influence Character will each have a role in the Overall Story besides their explorations of their own throughlines. From the Overall Story point of view we see all the story’s Overall Story Characters and identify them by the functions they fulfill in the quest to reach the Overall Story Concern. The Overall Story throughline is what brings all the characters in the story together and describes what they do with one another to achieve this Concern.

It is important to be able to separate the Main Character throughline from the Overall Story throughline to see your story’s structure accurately. It is equally important to make the distinction between the Influence Character and the Overall Story. Exploring these two characters’ throughlines in a story requires a complete shift in the audience’s perspective, away from the overall story that involves all the characters and into the subjective experiences that only these two characters have within the story. Thus, consider each of these throughlines individually.

The Main Character and the Influence Character will, however, each have at least one function to perform in the Overall Story as well. When we see them here, though, they both appear as Overall Story Characters. In the Overall Story all we see are the characteristics they represent in relation to the other Overall Story Characters.

So if your Main Character happens to be the Protagonist as well, then it is purely as the Protagonist that we will see him in the Overall Story. If your Influence Character is also an Archetypal Guardian, then his helping and conscience are all you should consider about that character in the Overall Story.

In every story, these two will at least engage in the Overall Story to represent the story’s Crucial Element and its dynamic opposite. It is possible the Main and Influence Characters could have no other relationship with the Overall Story than these single characteristics. The importance of the Main Character and the Influence Character to the Overall Story is completely in terms of the Overall Story characteristics assigned to them.

For the Relationship Story Throughline:

When looking at the characters in the Relationship Story Throughline, it is best to look at the Main and Influence Characters by their relationship with each other instead of their names. The Relationship Story Throughline is the We” perspective (that is first-person plural), so think in terms of the relationship between the Main and Influence Characters, not the characters themselves. Thus, the relationship between Dr. Richard Kimble and Sam Gerard” is the focus of the Relationship Story Throughline in The Fugitive, whereas The Verdict focuses on the relationship between Frank Galvin and Laura Fischer.”

For the Main Character Throughline:

When looking at the Main Character’s Throughline, all other characters are unimportant and should not be considered. Only the Main Character’s personal identity or essential nature is important from this point of view. What qualities of the Main Character are so much a part of him that they would not change even if he plopped down in another story? For example, Hamlet’s brooding nature and his tendency to over-think things would remain consistent and recognizable if he were to show up in a different story. Laura Wingfield, in The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams, would carry with her a world of rationalizations and a crippling inclination to dream if we were to see her appear again. These are the kinds of things to pay attention to in looking at the Main Character Throughline.

For the Influence Character Throughline:

When considering the Influence Character’s Throughline, look at their identity in terms of their impact on others, particularly the Main Character. Think of the Influence Character in terms of his name, but it’s the name of someone else, someone who can get under your skin. In viewing the Influence Character this way, it is easier to identify the kind of impact that he has on others. Obi Wan Kenobi’s fanaticism (on using the force) in Star Wars and Deputy Marshal Sam Gerard’s tenacity (in out-thinking his prey) in The Fugitive are aspects of these Influence Characters that are inherent to their nature. These qualities would continue to be so in any story in which they might be found.

Picking the proper Classes for

the Throughlines in your Story

Which is the right Class for the Main Character Throughline in your story? For the Overall Story Throughline? For the Relationship Story Throughline? For the Influence Character Throughline? Assigning the appropriate Dramatica Classes to the Throughlines of your story is a tricky but important process.

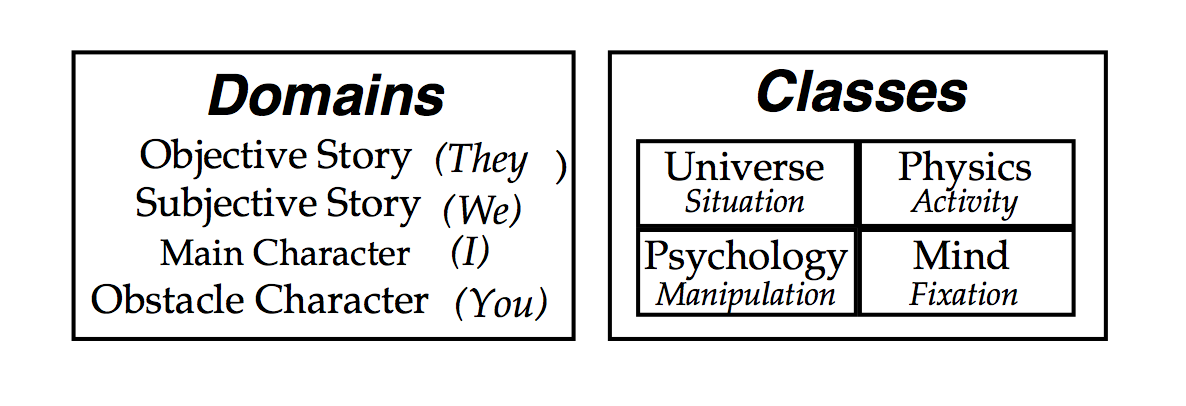

There are four Throughlines in a story: The Main Character, the Influence Character, the Relationship Story, and the Overall Story. These throughlines provide an audience with various points of view from which to explore the story. The four audience points of view can be seen as I, YOU, WE, and THEY. The audience’s point of view shifts from empathizing with the Main Character (I), to feeling the impact of the Influence Character (YOU). The audience’s point of view shifts to experiencing the relationship between the Main and Influence Character (WE), and then finally stepping back to see the big picture that has everyone in it (all of THEM). Each point of view describes an aspect of the story experience to which an audience is privy.

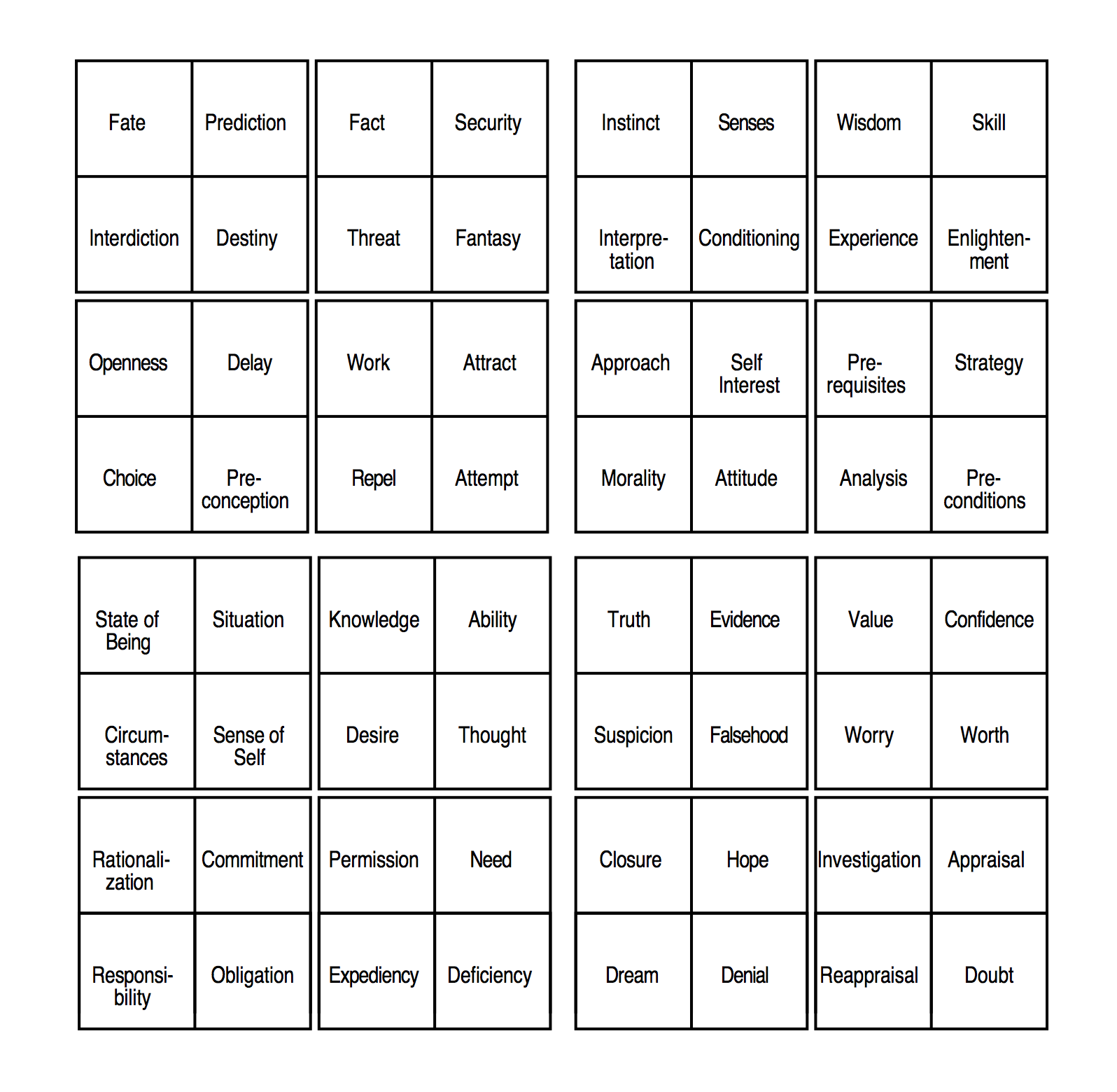

There are four Classes containing all the possible kinds of problems that can be felt in those throughlines (one Class to each throughline): Situation (Universe), Fixed Attitude (Mind), Activity (Physics), and Manipulation (Psychology). These Classes suggest different areas to explore in the story.

In Dramatica, a story will contain all four areas to explore (Classes) and all four points of view (throughlines). Each Class is explored from one of the throughlines. Combining Class and point of view into a Throughline is the broadest way to describe the meaning in a story. For example, exploring a Main Character in terms of his situation is different from exploring a Main Character in terms of his attitude, the activities that occupy his attentions, or how he is being manipulated. Which is right for your story?

Pairing the appropriate Class with the proper throughline for your story can be difficult. An approach you may find useful is to pick a throughline, adopt the audience perspective that throughline provides, and from that point of view examine each of the four Classes to see which feels the best.

Each of the following sections present the four Classes from one specific audience perspective. For best effect, adopt the perspective described in the section and ask the questions as they appear in terms of your own story. One set of questions should seem more important or relevant from that perspective.

NOTE: Selecting a point of view/Class relationship (or Throughline) says a lot about the emphasis you wish to place in your story. No pairing is better or worse than another. One pairing will be, however, most appropriate to what you have in mind for your story than the other three alternatives.

Dynamic Pairs of Throughlines

Each of the throughlines in a story can be seen as standing alone or as standing with the other throughlines. When selecting which Classes to assign the throughlines of your story, it is extremely important to remember two relationships in particular among the throughlines:

The Overall Story and Relationship Story throughlines are always a dynamic pair.

And….

The Main Character and Influence Character throughlines are always a dynamic pair.

These relationships reflect the kind of impact these throughlines have on each other in every story. The Main and Influence Characters face off throughout the story until one of them Changes (signaled by the Main Character Resolve). Their relationship in the Relationship Story will help precipitate either Success or Failure in the Overall Story (suggested by the Story Outcome).

What these relationships mean to the process of building the Throughlines in your story is that whenever you set up one Throughline, you also set up its dynamic pair.

For example, matching the Main Character throughline with the Situation class not only creates a Main Character Throughline of Situation in your story, it also creates an Influence Character Throughline of Fixed Attitude. Since Fixed Attitude is the dynamic pair to Situation in the Dramatica structure, matching one throughline to one of the Classes automatically puts the other throughline on the opposite Class to support the two throughlines’ dynamic pair relationship.

Matching the Overall Story throughline with Manipulation to create an Overall Story Throughline of Manipulation automatically creates a Relationship Story Throughline of Activity at the same time. The reasoning is the same here as it was for the Main and Influence Character throughlines. No matter which Class you match with one of the throughlines on the Dramatica structure, the dynamic pair of that class matches the dynamic pair of that throughline.

Who am I and what am I doing?

When looking from the Main Character’s perspective, use the first person singular (I”) voice to evaluate the Classes.

- If the Main Character’s Throughline is Situation (for example Luke in Star Wars or George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), questions like the following would arise: What is it like to be in my situation? What is my status? What condition am I in? Where am I going to be in the future? What’s so special about my past?

- If the Main Character’s Throughline is Activity (for example Frank Galvin in The Verdict or Dr. Richard Kimble in The Fugitive), questions like the following would be more appropriate: What am I involved in? How do I get what I want? What must I learn to do the things I want to do? What does it mean to me to have (or lose) something?

- If the Main Character’s Throughline is Fixed Attitude (for example Scrooge in A Christmas Carol), you would consider questions such as the following: What am I afraid of? What is my opinion? How do I react to something? How do I feel about this or that? What is it that I remember about that night?

- If the Main Character’s Throughline is Manipulation (for example Laura in The Glass Menagerie or Frank in In The Line of Fire), the concerns would be more like: Who am I really? How should I act? How can I become a different person? Why am I so angry, or reserved, or whatever? How am I manipulating or being manipulated?

Who are YOU and what are YOU doing?

When considering the Influence Character’s perspective, it is best to use the second person singular (You”) voice to evaluate the Classes. Imagine this as if one is addressing the Influence Character directly, where You” is referring to the Influence Character.

- If the Influence Character’s Throughline is Situation (for example Marley’s Ghost in A Christmas Carol), you might ask him: What is it like to be in your situation? What is your status? What condition are you in? Where are you going to be in the future? What’s so special about your past?

- If the Influence Character’s Throughline is Activity (for example Jim in The Glass Menagerie or Booth in In The Line of Fire): What are you involved in? How do you get what you want? What must you learn to do the things you want to do? What does it mean to you to have (or lose) something?

- If the Influence Character’s Throughline is Fixed Attitude (for example Obi Wan in Star Wars or Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?): What are you afraid of? What is your opinion? How do you react to that? How do you feel about this or that? What is it that you remember about that night?

- If the Influence Character’s Throughline is Manipulation (for example Laura Fisher in The Verdict or Sam Gerard in The Fugitive): Who are you really? How should you act? How can you become a different person? Why are you so angry, or reserved, or whatever? How are you manipulating or being manipulated?

Who are WE and what are WE doing?

When considering the Relationship Story perspective, it is best to use the first person plural (We”) voice to evaluate the Classes. We refers to the Main and Influence Characters collectively.

- If the Relationship Story’s Throughline is Situation (for example The Ghost & Hamlet’s pact in Hamlet or Reggie & Marcus’ alliance in The Client), consider asking: What is it like to be in our situation? What is our status? What condition are we in? Where are we going to be in the future? What’s so special about our past?

- If the Relationship Story’s Throughline is Activity (for example George & Martha’s game in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?): What are we involved in? How do we get what we want? What must we learn to do the things we want to do? What does it mean to us to have (or lose) something?

- If the Relationship Story’s Throughline is Fixed Attitude (for example Frank & Laura’s affair in The Verdict or Dr. Kimble & Sam Gerard’s relationship in The Fugitive): What are we afraid of? What is our opinion? How do we react to that? How do we feel about this or that? What is it that we remember about that night?

- If the Relationship Story’s Throughline is Manipulation (for example Obi Wan & Luke’s relationship in Star Wars): Who are we really? How should we act? How can we become different people? Why are we so angry, or reserved, or whatever? How are we manipulating or being manipulated?

Who are THEY and what are THEY doing?

When considering the Overall Story perspective, it is best to use the third person plural (They”) voice to evaluate the Classes. They refers to the entire set of Overall Story Characters collectively (for example protagonist, antagonist, sidekick, and so on).

- If the Overall Story’s Throughline is Situation (for example The Verdict, The Poseidon Adventure, or The Fugitive), consider asking: What is it like to be in their situation? What is their status? What condition are they in? Where are they going to be in the future? What’s so special about their past?

- If the Overall Story’s Throughline is Activity (for example Star Wars): What are they involved in? How do they get what they want? What must they learn to do the things they want to do? What does it mean to them to have (or lose) something?

- If the Overall Story’s Throughline is Fixed Attitude (for example Hamlet or To Kill A Mockingbird): What are they afraid of? What is their opinion? How do they react to that? How do they feel about this or that? What is it that they remember about that night?

- If the Overall Story’s Throughline is Manipulation (for example Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or Four Weddings and a Funeral): Who are they really? How should they act? How can they become different people? Why are they so angry, or reserved, or whatever? How are they manipulating or being manipulated?

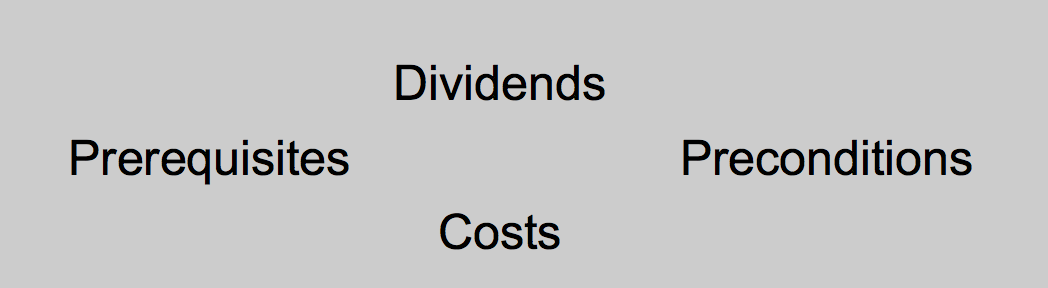

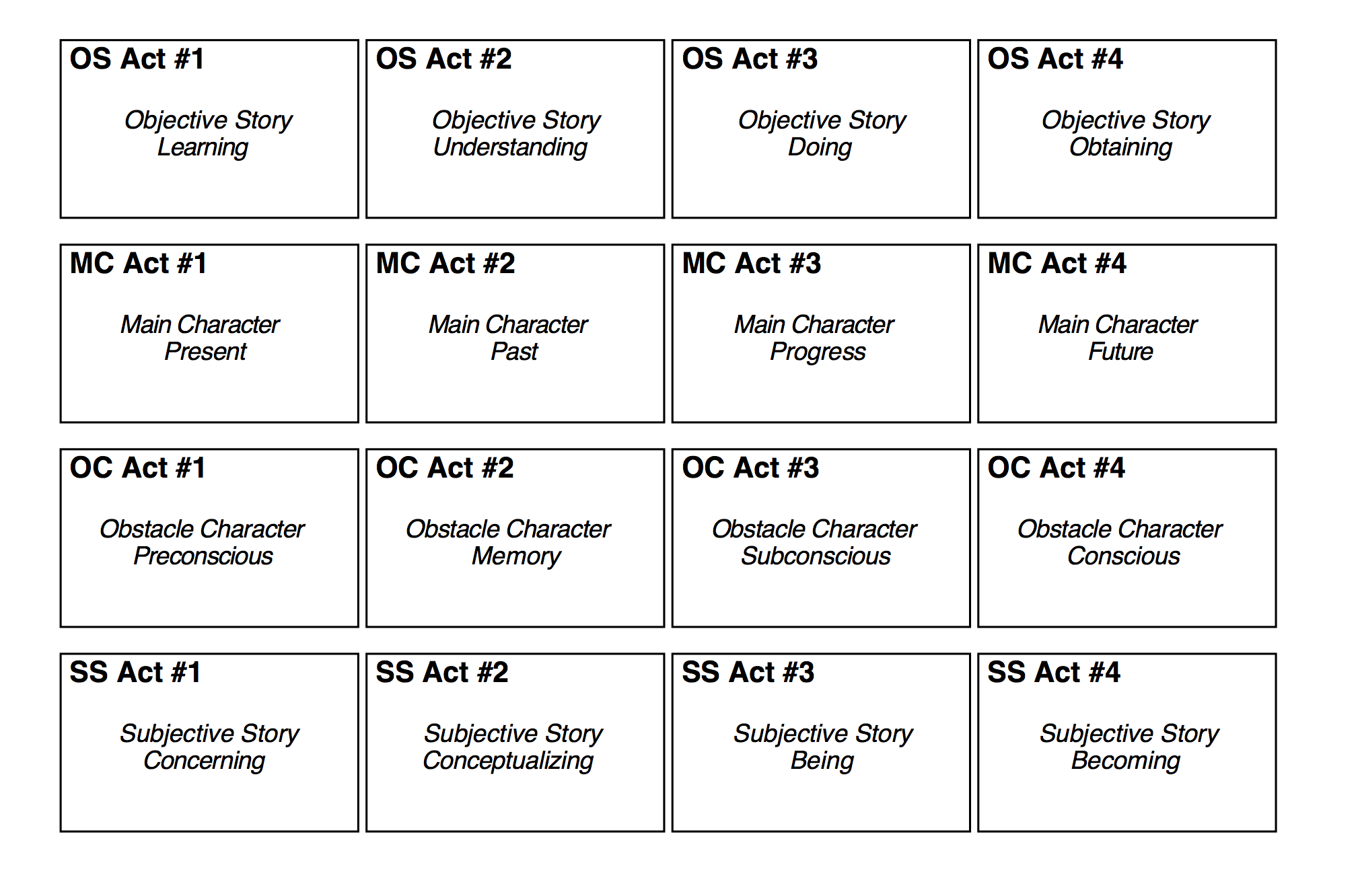

Selecting Plot Story Points

Plot Story Points come in two varieties: Static Story Points, and Progressive Story Points. Static Story Points are dramatic items such as Goal, Requirements, and Consequences, and may also include the Concerns of each throughline. Progressive Story Points deal with the order in which each Throughline's Types are arranged to become a throughline's Acts. In this section we shall first explore the issues involved in selecting the Static Plot Story Points, then turn our attention to what influence the order of Acts will have on our story's impact, and thus on our audience.

Static Plot Story Points

Story Goal

A story's Goal is most often found in the Overall Story Throughline for stories written in our culture. Apart from that bias, the story Goal might just as properly be in any of the four Throughlines. As we now consider how to select the Goal for our story, we need to know a little bit more about what a Goal does for an audience. What kinds of control over our audience we can exercise simply by choosing where we place the Goal?

An audience sees a story's Goal as being the central objective of the story. The goal will be of the same nature as the Concern of one of the four Throughlines. Which one depends on which throughline an author wants to highlight in his storytelling. For example, suppose your Main Character and his experiences are the most important thing to you, the author. Then you will most likely want to make the Main Character's Concern your story Goal as well. On the other hand, if your story is about a problem that is affecting everyone, you will probably want to make the Overall Story Throughline Concern your story Goal.

Each throughline will have its own Concern. When the audience considers each throughline separately, it will focus on that Concern as being the principal objective from that point of view. When the audience considers the story as a whole, however, it will get a feel for which throughline is most highlighted by the author's storytelling, and will see that throughline's Concern as the overall story Goal.

Since emphasis is a gray-scale process, the story Goal may be a highly focused issue in some stories and of lesser concern in others. In fact, you may stress all four throughlines equally which results in an audience being unable to answer the question, what was this story about? Just because no overall Goal is identifiable does not mean the plot necessarily has a hole. It might mean the issues explored in the story are more evenly considered in a holistic sense, and the story is simply not as Goal-oriented. In contrast, the Concern of each Throughline must appear clearly in a complete story. Concerns are purely structural story points developed through storytelling, but not dependent on it.

When selecting a Goal, some authors prefer to first select the Concerns for each Throughline. In this way, all the potential objectives of the story are predetermined and the author then simply needs to choose which one to emphasize. Other authors prefer not to choose the Goal at all, since it is not an essential part of a story's structure. Instead, they select their Concerns and then let the muse guide them in how much they stress one throughline over another. In this way, the Goal will emerge all by itself in a much more organic way. Still, other authors like to select the Goal before any of the Concerns. In this case, they may not even know which Throughline the Goal is part of. For these kinds of author, the principal question they wish to answer is, what is my story about? By approaching your story Goal from one of these three directions, you can begin to create a storyform that reflects your personal interests in telling this particular story.

There are four different Classes from which to choose our Goal. Each Class has four unique Types. In a practical sense, the first question we might ask ourselves is whether we want the Goal of our story to be something physical or something mental. By deciding this we are able to limit our available choices to Situation or Activity (physical goals), or Fixed Attitude or Manipulation (mental goals). Instantly we have cut the sixteen possible Goals down to only eight.

Next we can look at the names of the Types themselves. In Situation: Past, Progress, Present, and Future. In Activity: Understanding, Doing, Learning, and Obtaining. In Fixed Attitude: Memory, Impulsive Responses, Contemplation, and Innermost Desires. In Manipulation: Developing A Plan, Playing A Role, Conceiving An Idea, and Changing One's Nature. Some are easy to get a grip on; others seem more obscure. This is because our culture favors certain Types of issues and doesn't pay as much attention to others. Our language reflects this as well so even though the words used to describe the Types are accurate, many of them need a bit more thought and even a definition before they become clear. (Please refer to the appendices of this book for definitions of each.)

Whether you have narrowed your potential selections to eight or just jump right in with the whole sixteen, choose the Type that best represents the kind of Goal you wish to focus on in your story.

Requirements

Requirements are the essential steps or circumstances that must be met to reach the story's Goal. If we were to select a story's Requirements before any other appreciation, it would simply be a decision about the kinds of activities or endeavors we want to concentrate on as the central effort of our story. If we have already selected our story's Goal, however, much has already been determined that may limit which Types are appropriate to support that Goal.

Although the model of dramatic relationships set up in the Dramatica software can discover which are the best candidates to choose for a given appreciation, the final decision must rest with the author. Trust your feelings, Luke," says Obi Wan to young Skywalker. When selecting story points that advice is just as appropriate.

Consequences

Consequences are the results of failing to achieve the Story Goal. Consequences are dependent on the Goal, though other story points may change the nature of that dependency. Consequences may be what will happen if the Goal is not achieved, or currently suffered and will continue or worsen if the Goal is not achieved. You should select the Type that best describes your story's risk.

One of the eight essential questions asks if the direction of your story is Start or Stop. A Start story is one in which the audience will see the Consequences as occurring only if the Goal is not achieved. In a Stop story, the audience will see the Consequences already in place, and if the Goal is not achieved the Consequences will worsen.

Choosing the Type of Consequence does not control Start or Stop, and neither does choosing Start or Stop determine the Type of Consequence. How the Consequence will come into play, however, is a Start/Stop issue. Since that dynamic affects the overall feel of a story, it is often best to make this dynamic decision of Start or Stop before trying the structural one of selecting the Consequence Type.

Forewarnings

Forewarnings signal the imminent approach of the Consequences. At first, one might suspect that for a particular Type of Consequences, a certain Type of Forewarnings will always be the most appropriate. There are relationships between Forewarnings and Consequences that are so widespread in our culture that they have almost become story law. But in fact, the relationship between Forewarnings and Consequences is just as flexible as that between Requirements and Goal.

Can the Forewarnings be anything at all then? No, and to see why we need look no further than notice that Consequences and Forewarnings are both Types. They are never Variations, or Elements, or Classes. But, within the Types, which one will be the appropriate Forewarnings for particular Consequences depends on the impact of other story points.

When selecting the Type of Forewarning for your story, think of this appreciation both by itself and with the Consequences. By itself, examine the Types to see which one feels like the area from which you want tension, fear, or stress to flow for your audience or characters. Then, with the Consequences, decide if you see a way in which this Type of Forewarning might be the harbinger that will herald the imminent approach of the Consequences. If it all fits, use it. If not, you may need to rethink either your selection for Forewarnings or your choice for Consequences.

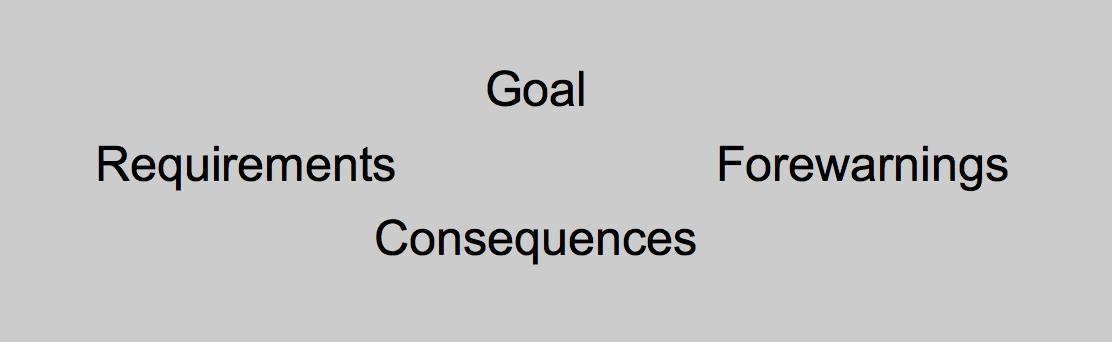

Driver and Passenger Plot Story Points

The eight static plot story points should be seen in relation to one another. Each of them affects how the others appear, and a rise in the presence of one will always begin a ripple in the presence of the others.

One way to predict their relationship with one another in your story is to arrange them into two quads and then explore the relationships that these quads create. The nature of these story points will be different for every story, however the story points will always have these driver and passenger quad arrangements.

Driver Plot Story Points

Passenger Plot Story Points

Dividends

Dividends are the benefits added bit by bit on the way to the Goal. Goal, Requirements, Consequences, and Forewarnings are all Driver Story Points in Plot. Dividends are the first of the Passenger Story Points. We see it used in storytelling more as a modifier than a subject to itself. Still, since authors may choose to stress whatever they wish, Dividends may be raised to the forefront in a particular story and take on significance far beyond their structural weight.

No matter what emphasis you give Dividends in your story, they are still modifiers of the Goal. When selecting the Type of Dividends for your story, consider how well your choice dovetails with your Goal. Sometimes Dividends are close in nature to the Goal, almost as natural results of getting closer to the Goal. Other times Dividends may be different in nature than the Goal, and are simply positive items or experiences that cross the characters' paths during the quest.

As with the Driver Story Points, this choice is not arbitrary. The dynamics that control it, however, are so many and varied that only a software system can calculate it. Still, when you answer the essential questions, it is likely your writing instincts become so fine-tuned to your story that you sense which kinds of Dividends seem appropriate to the Goal under those particular dynamic conditions.

Costs

Costs function much like negative Dividends. They are the harmful effects of the effort to reach the Goal. Look at the Requirements for your story and see what Type of Costs might make that effort more taxing. Look at the Consequences for your story and see what Type of Costs might seem like an indicator of what might happen if the Goal is not achieved. Look at the Forewarnings and determine the Type of Costs that increases the Forewarnings, or possibly obscures the Forewarnings from your characters. Finally, look at the Dividends and try to find a Type for Costs that balances the positive perks. To balance Dividends, Costs need not be an exact opposite, but simply have the opposite (negative) effect on the characters.

Prerequisites

Prerequisites determine what is needed to begin meeting the Requirements. When selecting Prerequisites, keep in mind they are in your story as essential steps or items that must be met or gathered to attempt a Requirement. The Type of Requirements much more heavily influences the appropriate Type of Prerequisites than the Type of Goal.

Prerequisites may open the opportunity for easy ways to bring in Dividends, Costs, or even Preconditions (which we shall discuss shortly.) Certain Types of considerations may be more familiar to you than others because of your personal life experience. They will likely be a better source of material from which to draw inspiration. Choosing a familiar Type will help you later when it becomes time to illustrate your story points in Storyencoding.

Preconditions

Preconditions are non-essential steps or items that become attached to the effort to achieve the Goal through someone's insistence. A keen distinction here is that while Prerequisites are almost always used with the Requirements in a story, Preconditions are likely to apply to either Requirements or the Goal itself. Take both Goal and Requirements into account when selecting Preconditions.

Think about the sorts of petty annoyances, frustrations, and sources of friction with which your characters might become saddled, in exchange for help with some essential Prerequisite. If you were one of your characters, what kind of Preconditions would most irritate you?

Story Points of this level often appear as a background item in storytelling. Draw on your own experiences while making this selection so the level of nuance required can grow from your familiarity.

Plot Story Point Examples:

GOAL:

The Story Goal in Hamlet is Memory: Everyone wants to be comfortable with the memory of King Hamlet. Most wish to do this by erasing the memory of his unexpected death, but Hamlet wants to keep it alive and painful.

The Story Goal in The Godfather is Obtaining: The Overall Story goal of the Godfather is for the Corleone family to reclaim their place of power and find a new Godfather to preserve this status.

REQUIREMENTS:

The Story Requirements in Hamlet are Innermost Desires: Hamlet must get King Claudius to expose his true nature, his lust for power and Queen Gertrude, before anyone will believe Hamlet's accusations.

The Story Requirements in The Godfather are Doing: For a new Don Corleone to regain his family's former stature and power, he must do things that prove his superiority in the rivalry among the New York families. He succeeds with the hits on Barzini, Tessio, and Moe Green on the day Michael settles all family business.

CONSEQUENCES:

The Story Consequences in Hamlet are The Past: If the characters forget King Hamlet's murder, a repetition of the past murder will (and does) occur. King Claudius kills Hamlet to preserve his position as king.

The Story Consequences in The Godfather are Changing One's Nature: If the Corleone family fails to reclaim their power they will be forced to become one of the secondary families in the New York crime scene.

FOREWARNINGS:

The Story Forewarnings in Hamlet are Changing One's Nature: Hamlet starts becoming the crazy person he is pretending to be. This alerts everyone, including King Claudius who plots against Hamlet, that Hamlet will not let the memory of his father die peacefully.

The Story Forewarnings in The Godfather are Progress: When Don Corleone realizes that it was the Barzini family orchestrating his downfall, the Barzini's have already made progress towards becoming the new top family in New York. The progress of the loyalty of other families falling in line with Barzini threatens to cut off Michael's chance to reestablish his family's stature.

DIVIDENDS:

The Story Dividends in Hamlet are Developing A Plan: There is a general sense of creative freedom among the members of King Claudius' court typified by Polonius' advice to Laertes on how to take advantage of his trip abroad. Hamlet finds that suddenly many ordinary things help in his objective of manipulating the truth out of King Claudius, and he takes pleasure in them. The play becomes a trap; every discussion becomes an opportunity to find out people's true opinions. These are all dividends of the efforts made in this story.

The Story Dividends in The Godfather are The Future: The struggle in organized crime over how distribution is costly, but it lays the groundwork for what will one day be their biggest moneymaking industry. Michael's choice of murders make him New York's new Godfather and ensures his family a safe move to Las Vegas in the future.

COSTS:

The Story Costs in Hamlet are Understanding: In Hamlet, understanding is a high price to pay—sometimes too high. King Claudius comes to the understanding that Hamlet is on to him and won't stop pushing until Hamlet avenges his father's death. Ophelia comes to the understanding that Hamlet does not love her and is also responsible for her father's death, so she loses her mind. Queen Gertrude comes to the understanding that her son likely is insane and her new husband is a murderer, and so on.

The Story Costs in The Godfather are Innermost Desires: As the struggle for power in New York's underground continues, all the people involved suffer emotional damage which hits them in their subconscious. For example, Sonny's death aggravates Tom's pain not being the Don's son. Don Corleone suffers for the future of his family as his sons die or become criminals like himself. Sonny suffers the insult of living with a brother-in-law who beats Sonny's sister. The Turk realizes his fears when the murder attempt on the Don only wounds him. Kaye buries her suspicions that her husband is in organized crime.

PREREQUISITES:

The Prerequisites in Hamlet are Future: Before Hamlet can begin the work of exposing Claudius, he must know when the appropriate people will be around so he can put his plans (such as the play) into place.

The Prerequisites in The Godfather are Playing A Role: Because Michael avoids being in his family's business, others must fill in the temporary vacancy left by his wounded father. Michael himself believes his involvement with the Mafia is temporary until the point when he has become the new Godfather.

PRECONDITIONS:

The Preconditions in Hamlet are Obtaining: Hamlet needs hard evidence of his uncle's murderous actions—his own preconditions are that he cannot allow himself to go on the word of the Ghost alone.

Preconditions in The Godfather are Impulsive Responses: For someone to be a good Don, they have to have the correct kinds of immediate responses. Sonny was not a good Don, because he was too hotheaded. Fredo isn't a good candidate because fumbles and drops his gun during his father's shooting. A precondition, which Michael fulfills, is that he has the instincts to guide the family well. He displays these when he has no frightened responses while protecting his father at the hospital and when he immediately insists on killing the Turk himself. He shows this once again when he accepts the news of Tessio's betrayal without blinking an eye or betraying himself at any point through Impulsive Responses. When Sonny's hotheaded attempts to muscle the Corleone's back to the top failed, it became clear there are preconditions set about whom could be the next Godfather. Only someone with a steel control over his Impulsive Responses is cool enough to lead the Corleone family successfully back to prominence.

Summary On Selecting Static Plot Story Points

We have examined some of the considerations that go into selecting Static Plot Story Points. Independent of any other dramatics, any Type might be selected for any of these story points. When more structural story points already are chosen, however, one must consider their impact as well in making a selection.

In Western culture, the Goal is most often found in the Overall Story Throughline; however, it might be equally appropriate in any of the four Throughlines. With the eight essential questions the relationship between the Static Plot Story Points may place them evenly throughout the Throughlines, or may favor some Throughlines more than others.

These eight Static Plot Story Points are not solely structural items (though grounded in structure). Modulating their emphasis in the storytelling also affects them.

Static & Progressive Plot Story Points

There are two kinds of plot story points, Static ones which do not change and Progressive ones that transform as the story continues. To see each kind of story point in your story you need to alter your point of view.

Static plot story points are Goal, Requirements, Consequences, Forewarnings, Dividends, Costs, Prerequisites, and Preconditions. Since these static plot story points remain constant in nature from the beginning of the story to the end, look at them as they relate to the story as a whole, as if the story is one single thing. These story points should be in effect no matter what part of the story you look at. The Goal will always be present and identifiable, the Consequences will always be looming. Their presence at any point in the story may be understated or right up front, but the clearer they remain throughout the story, the stronger the story's plot will be from this point of view.