Filtered Analysis

Be-er Female stories

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

The Help

Ford V Ferrari

The Big Lebowski

Moonlight

Sophie’s Choice

Brief Encounter

The Social Network

Ida

The Sixth Sense

The Producers

La Dolce Vita

Rebecca

Field of Dreams

Let The Right One In

The Sound of Music

My Brilliant Career

Network

Jerry Maguire

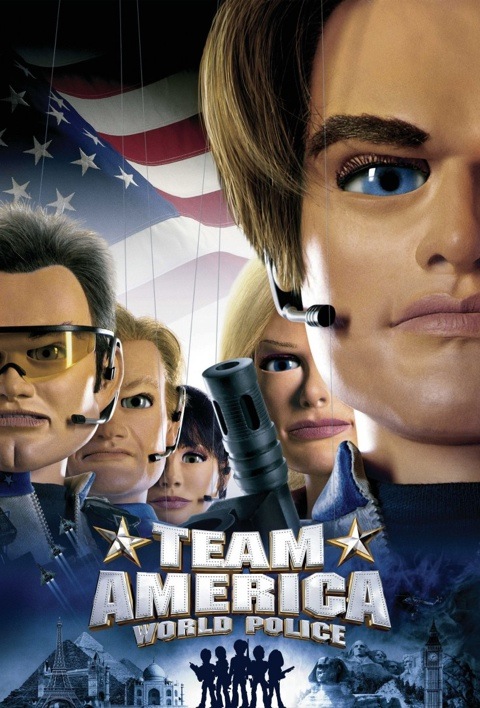

Team America: World Police

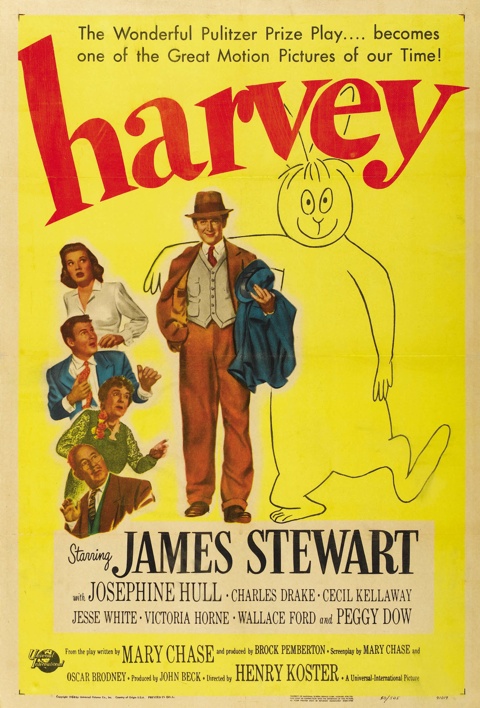

Harvey

Amélie

A Face in the Crowd

City of God

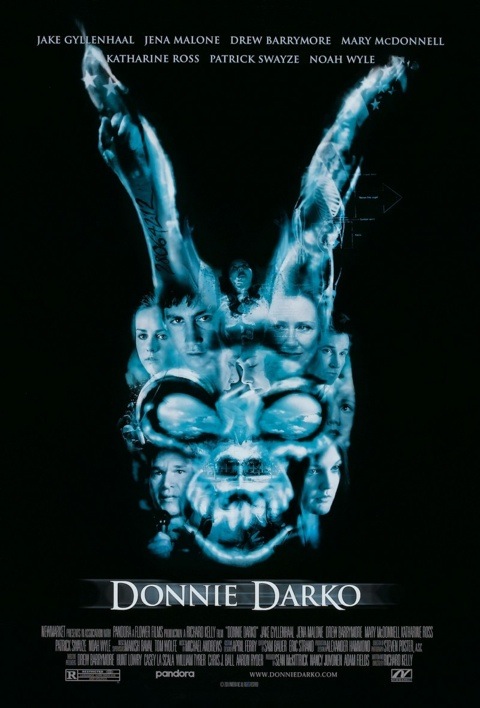

Donnie Darko

Mrs. Miniver

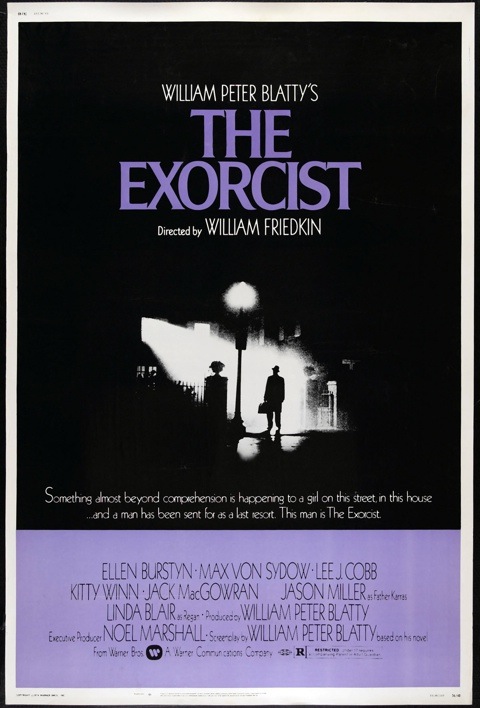

The Exorcist

Chicago

The Others

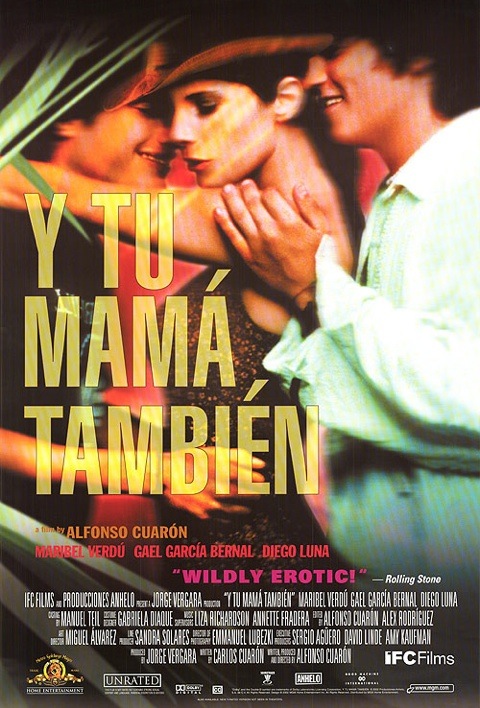

Y tu mamá también

The Contender

The American President

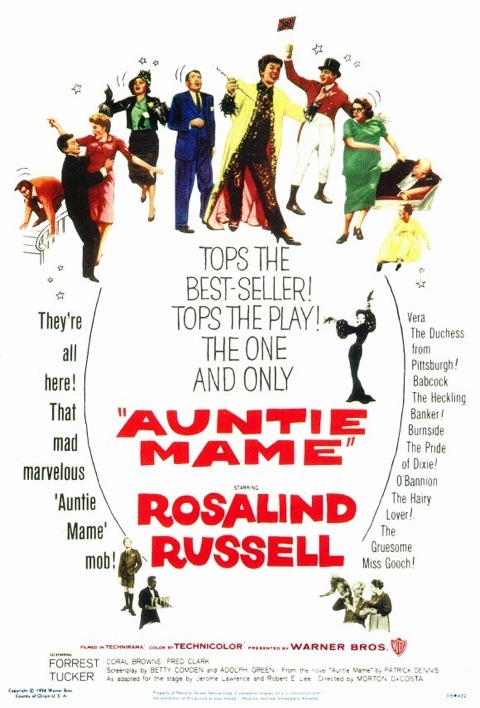

Auntie Mame

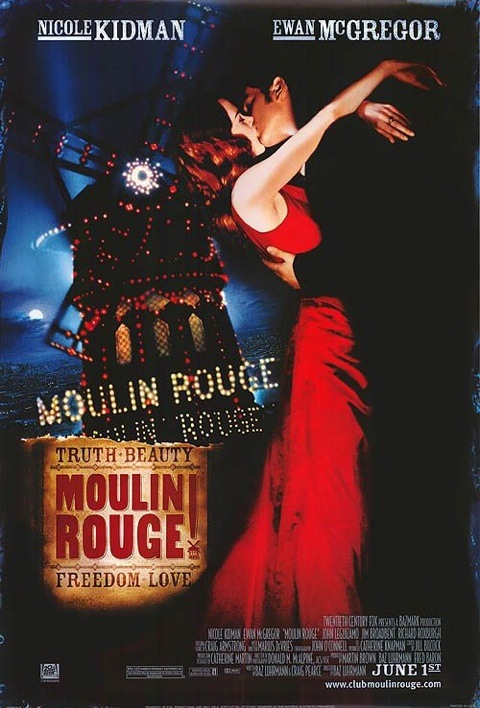

Moulin Rouge!

Desk Set

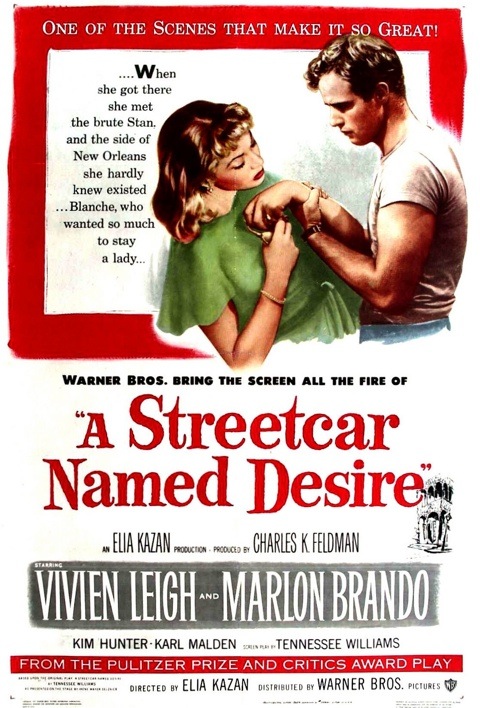

A Streetcar Named Desire

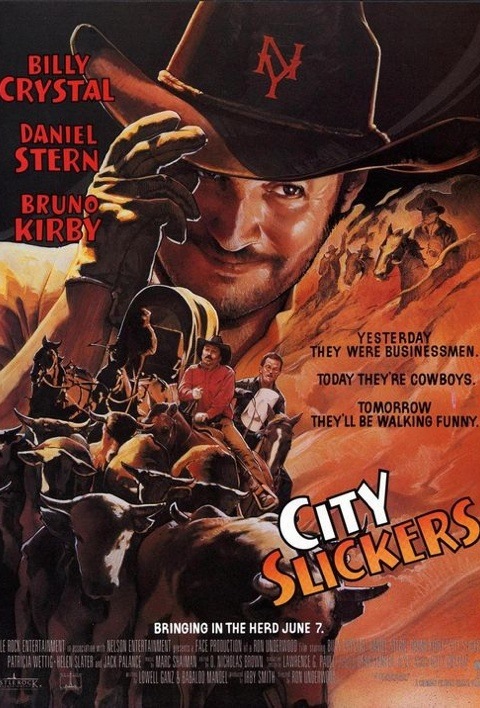

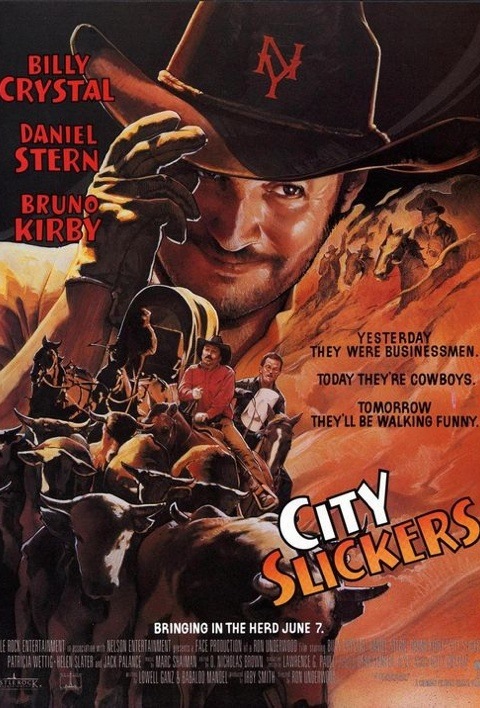

City Slickers

City Slickers

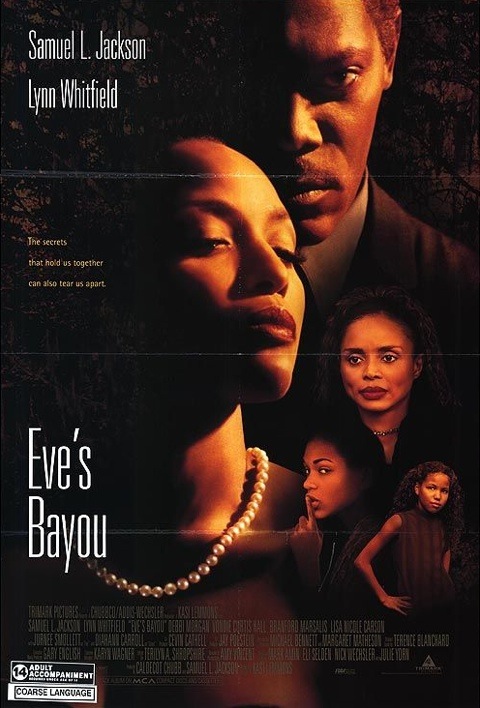

Eve’s Bayou

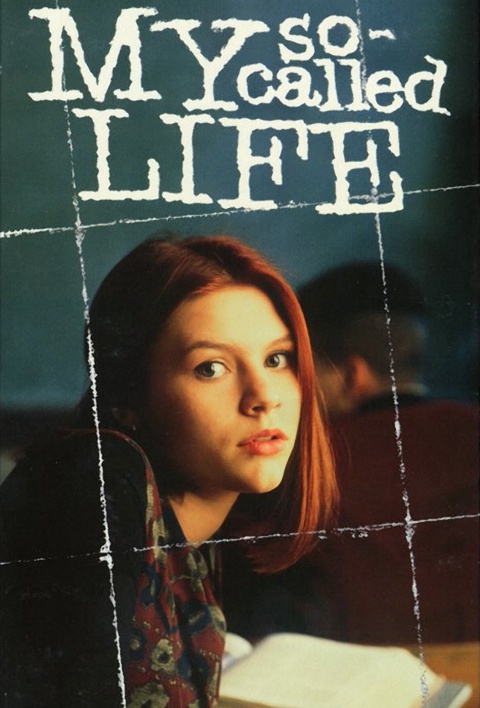

My So-Called Life

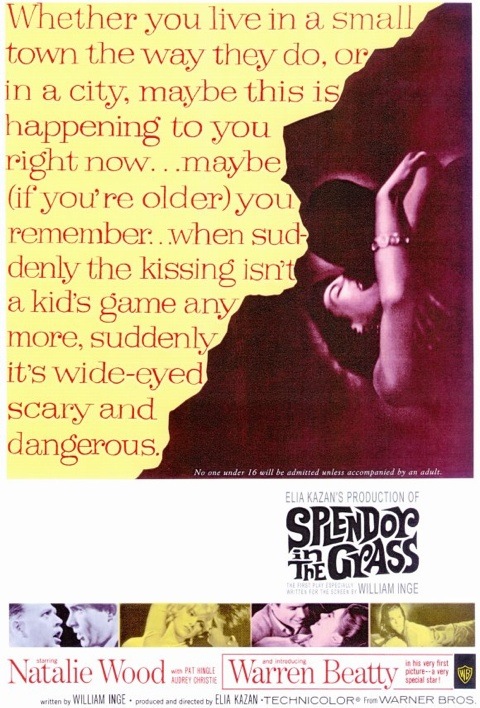

Splendor in the Grass

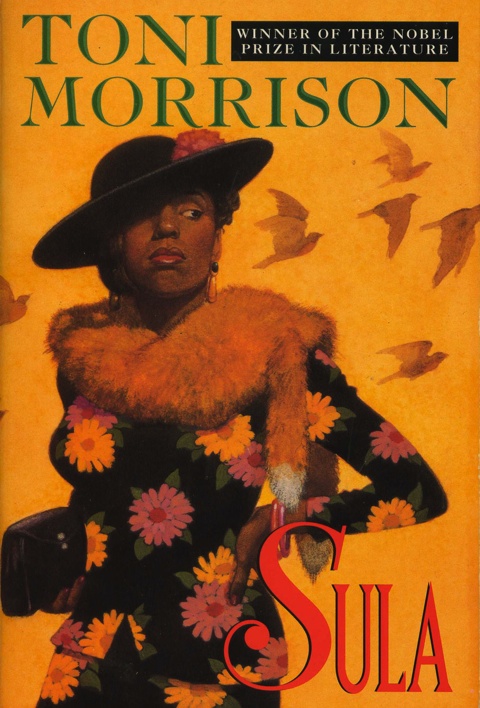

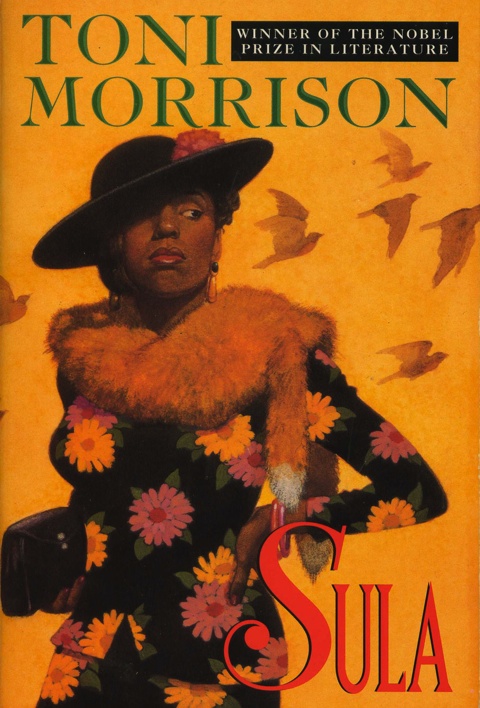

Sula

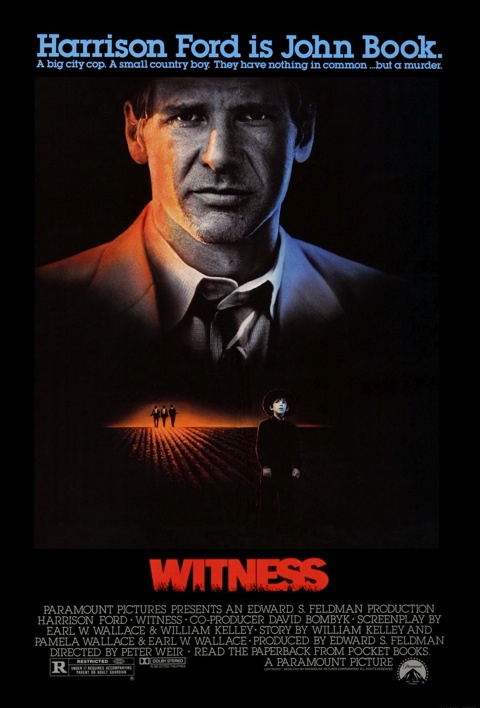

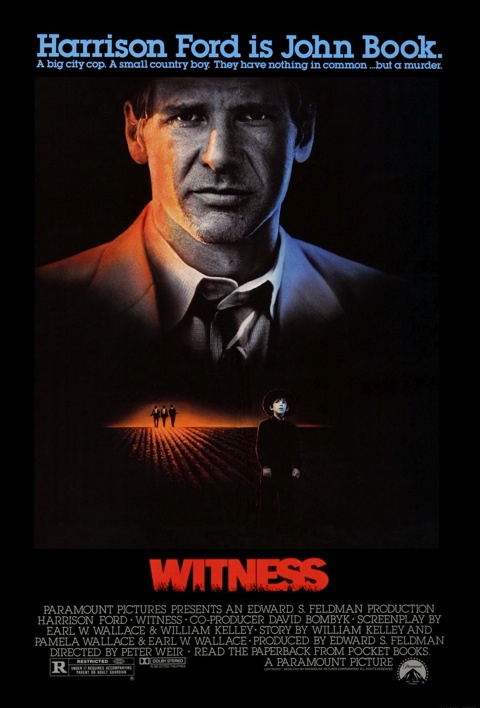

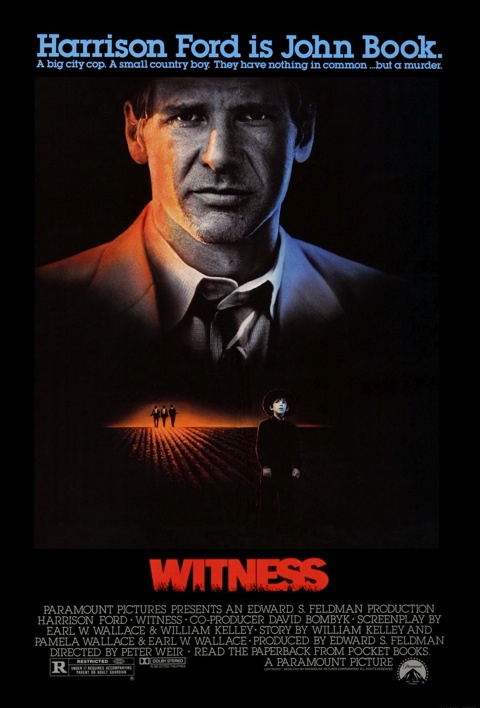

Witness

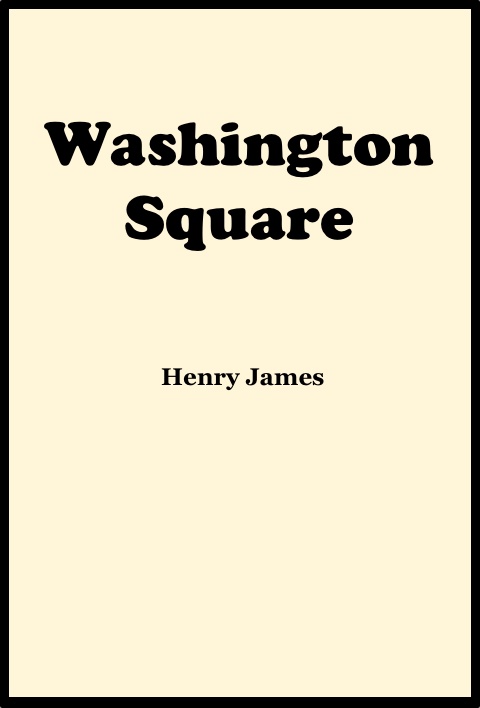

Washington Square

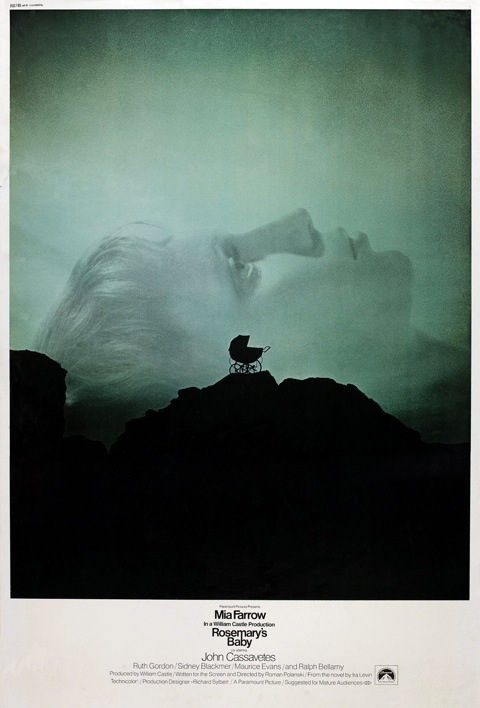

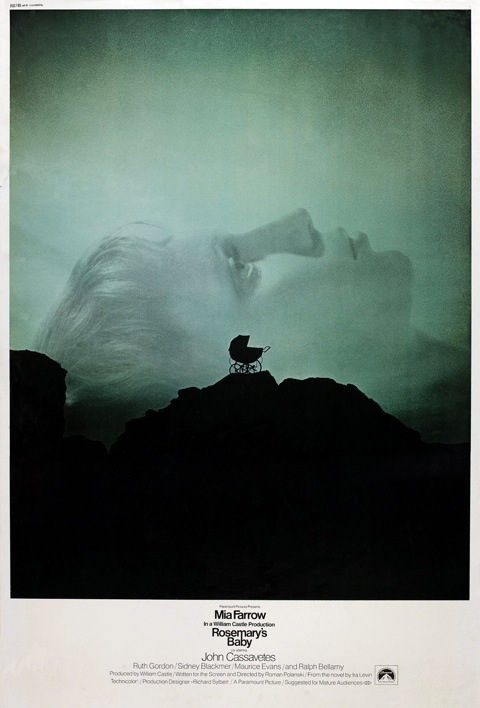

Rosemary’s Baby

The Glass Menagerie

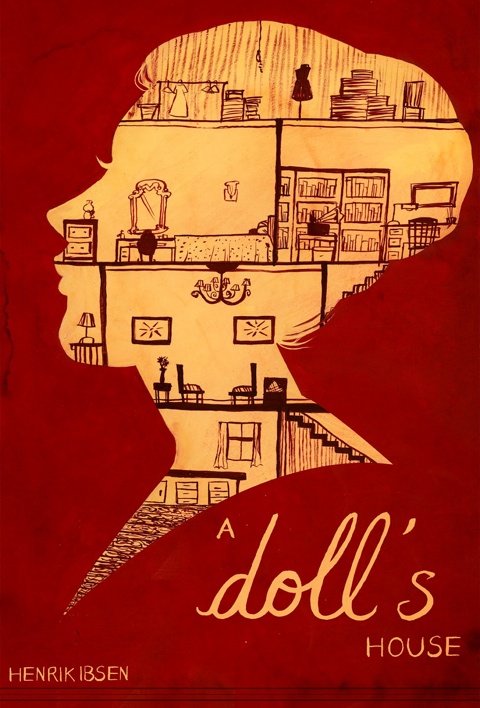

A Doll’s House

Be-er

Main Character Approach

Washington Square

When faced with a problem, Catherine’s preference is to solve it internally, as illustrated in a conversation between her father and Aunt Almond:

“‘And, meanwhile, how is Catherine taking it?’ ‘As she takes everything—as a matter of course.’ ‘Doesn’t she make a noise? Hasn’t she made a scene?’ ‘She is not scenic.’” (James 69)

Once her father refuses her lovers’ suit, Catherine contemplates:

The idea of a struggle with her father, of setting up her will against his own, was heavy on her soul, and it kept her quiet, as a great physical weight keeps us motionless. It never entered into her mind to throw her lover off; but from the first she tried to assure herself that there would be a peaceful way out of their difficulty. The assurance was vague, for it contained no element of positive conviction that her father would change his mind. She only had the idea that if she should be very good, the situation would in some mysterious manner improve. To be good she must be patient, outwardly submissive, abstain from judging her father too harshly, and from committing any act of open defiance. (James 81)

Rosemary’s Baby

Rosemary tries to accommodate everyone before herself. She agrees to the dinner invitation with the Castevets, even though she doesn’t want to go. Then she feels obligated, but tells Guy that it’s all right if he doesn’t want to attend. When Rosemary learns she is pregnant, she lets the Castevets push her into giving up a doctor she likes for one they recommend. Even though she is in great pain, she finds a way to adapt to it rather than confront her doctor:

Tiger: You’ve been in pain since November and he (Dr. Sapirstein) isn’t doing anything for you?

Rosemary: He says it’ll stop.

Joan: Why don’t you see another doctor?

Rosemary shakes her head.

Rosemary: He’s very good. He was on “Open End.”

Witness

Rachel adapts to the situations she finds herself in: she accepts being detained by Book and taken to his sister’s house:

SAMUEL: But do we have to stay here?

RACHEL: No, we do not. Just for the night.

Rachel accommodates Book’s presence on the farm; she remains in the Amish community, even though she has doubts about her faith; etc.

Sula

From childhood, Nel copes with problems internally:

“...the girl became obedient and polite. Any enthusiasms that little Nel showed were calmed by the mother until she drove her daughter’s imagination underground” (Morrison, 1973, p. 18).

When Nel finds Jude and Sula naked in her bedroom, she thinks:

They are not doing that. I am just standing here seeing it, but they are not really doing it…I just stood there seeing it and smiling, because maybe there was some explanation, something important that would make it all right. (Morrison, 1973, p. 105)

After Jude leaves Nel, she winds up her anger into an imaginary gray ball so that she may function.

Female

Main Character Mental Sex

Sula

Nel uses Sula to creates balance within herself and environment.

A Doll’s House

Nora effectively assesses what she needs to do to maintain the balance in her marriage.

Witness

When Amish elders object to harboring Book—because if he dies, the policemen will come, investigate, disrupt, cause publicity, etc.,—Rachel looks at the bigger picture. She responds that they must make it so that they never find his body, without going into details of how they would accomplish that.

Rosemary’s Baby

The female mental sex character resolves problems by comparing surpluses to deficiencies, and then taking steps to create a balance. When Guy first refuses to go to the Castevets for dinner, even though Rosemary makes it clear that she promised Mrs. Castevet, she begins reasoning out loud why they should stay home—creating a surplus of reasons acquiesce to Guy’s wishes. She doesn’t push Guy, but eventually he says, “Let’s go.” When her pregnancy becomes a seeming never-ending agony, and no one will listen to her, she throws a party where her friends can assess her shocking physical and emotional condition and push her to see a new doctor. When she grows weary of Minnie’s meddling, she accepts Minnie’s “herbal” drink, but then pours it down the drain. Thus she is dealing with the immediate surplus, but not yet taking steps to resolve the whole problem. When she discovers the truth about her baby, she is armed with a butcher knife as if she is willing to strike at one of the perpetrators, or even her baby. But she is confronted with a different inequity: the need of her baby. The story ends with Rosemary “becoming” the mother to her child, having seen the real deficiency in the situation, the baby’s lack of a mother.